This week marks the beginning of spring. And now that it’s here, summer is right on deck. That of course means a few months of sustained sunshine, outdoor festivals, and dining al fresco.

This summer, though, could also mean terror. That’s because this year’s mosquitoes will bring with them more than the usual annoyances and everyday itching. These mosquitoes could mean outbreak, paranoia, and fear. This, inarguably, is the summer of Zika.

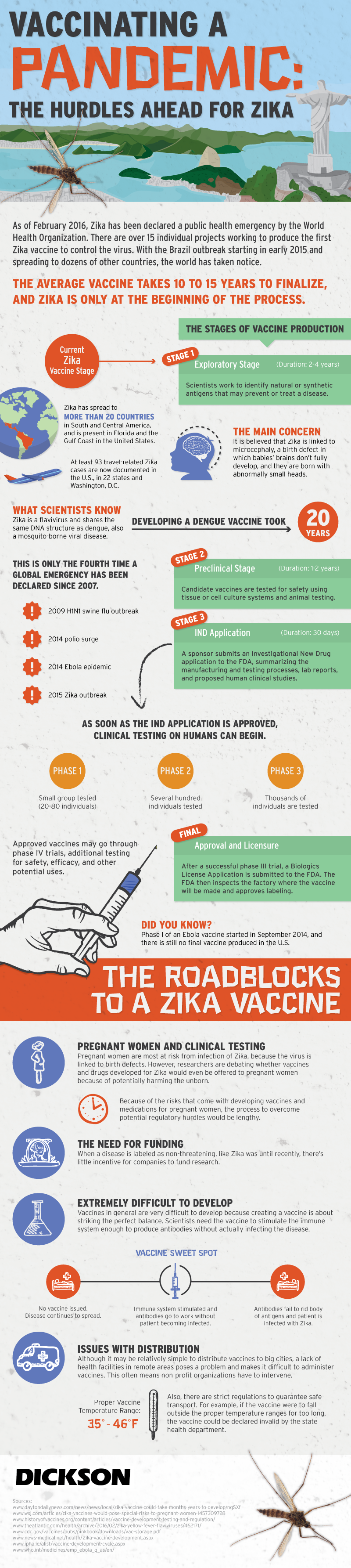

As we spoke about In February, the World Health Organization has declared the Zika outbreak as a public health emergency. Zika has spread to more than 20 countries, and counting. As of Thursday, there were nearly 450 people infected with Zika in the U.S., 93 of which had been diagnosed as travel-related infections, across 22 states.

While Zika isn’t life-threatening to most adults, the main concern is its link, albeit unproven, to microcephaly, a birth defect in which babies’ brains don’t fully develop. It’s that unknown that has made the production of a Zika vaccine so tricky.

In a best-case scenario, developing a vaccine is difficult. Researchers pore over a multitude of combinations and correlations. Scientists work to strike the perfect balance: stimulate the immune system enough to produce antibodies but avoid actually infecting the disease. From concept to market, the average process takes about 15 years.

That process encompasses three stages: exploratory, preclinical, and Investigational New Drug, or IND. After passing through those stages, testing generally begins, again, in three phases: on 20 to 80 people (Phase I), several hundred people (Phase II), and ultimately several thousand (Phase III).

This process, for any vaccine, can be protracted and byzantine. The vaccine for the dengue virus, a sometimes deadly mosquito-borne germ that’s a close cousin of Zika, took over 20 years to develop. In September 2014, an Ebola vaccine entered Phase I testing, but progress has since halted; there is still no legitimate Ebola vaccine produced in the U.S.

In Zika’s case, the process is even more complicated (paywall) because of the link the virus has had to birth defects. The risks, and regulations, inherent in developing a vaccine for pregnant women are innumerable. Researchers and scientists are split on whether to even offer a Zika vaccine to pregnant women due to fear of harming the unborn.

Other factors contribute to the potential vaccine’s plight. A lack of funding, inadequate distribution, deficient administration, and improper transportation and storage—storing the vaccine outside the proper temperature range can lead to its invalidation by the health department—all serve as sizable roadblocks.

Despite the obstacles, there is hope. According to NBC News, a new dengue vaccine may form the basis for a Zika version. The dengue vaccine is currently being tested in Brazil in a 17,000-person volunteer trial. In theory, researchers would add on a Zika component to help shorten development time.

Until that plays out and a vaccine is available, there are things you can do now, like spray for adult mosquitoes and eliminate standing water to reduce their ability to breed. Whether you’re looking forward to outdoor festivals or alfresco dining as the seasons continue to change, do all you can to protect yourself and don’t forget to stop and enjoy spring.